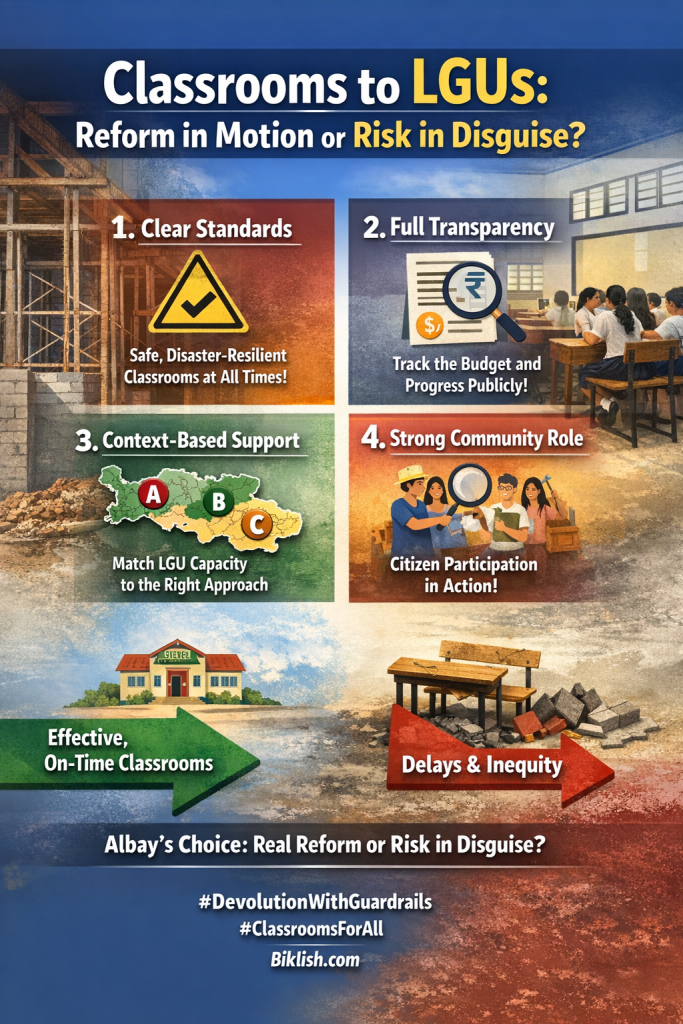

Just recently, Albay Governor Noel Rosal proudly announced that Department of Education (DepEd) is partnering with local government units (LGUs) in Albay and nationwide to expedite classroom construction, downloading funds directly to LGUs for faster, more accountable, and higher-quality building, with over PhP 85 billion in 2026 for school facilities construction. Well, it sounds like a long-overdue fix. Mas harani an LGU sa eskwelahan, mas makaskass dapat an coordination, asin mas madali maipaabot an mga reklamo kan mga principal, maestra, asin mga maguran. In theory, this shift cuts red tape, avoids the usual “follow-up sa Manila” cycle, and helps ensure classrooms are ready by School Year 2026–2027.

But here’s the catch: devolution is not automatically delivery.

Moving the function closer to the people only works if we also move the systems, safeguards, and capacity needed to deliver quality classrooms—on time, within budget, and built to last.

So yes, this can be reform in motion. But it can also become risk in disguise—if the guardrails are weak.

Guardrail 1: Standards must stay firm, even if delivery becomes local

Speed is good. But speed without standards is how you get fast defects.

Bicol is disaster-prone. So classrooms must meet strict requirements for:

- structural safety and durability

- climate and disaster resilience (typhoons, floods, even ashfall realities)

- ventilation, lighting, and basic learning comfort

- WASH facilities and accessibility

Devolution should not mean “bahala na.” It should mean: LGUs build faster, but within non-negotiable national standards.

Guardrail 2: Transparency should be public, not just “reported”

If billions for classrooms will flow through local implementation, the public should see—clearly and easily—where the money goes.

Every LGU should publish and regularly update:

- the list of projects (location, number of classrooms, scope)

- budgets and timelines

- contractors and procurement results

- monthly progress reports with photos

- reasons for delays or change orders (if any)

Because the simplest anti-corruption and anti-delay tool is visibility:

when people can see the project, it’s harder to fake progress.

Guardrail 3: Context-based implementation—because not all LGUs are equally ready

This is the biggest missing piece in many devolution reforms: capacity is uneven.

If we pretend all LGUs can implement equally, we will reproduce inequality in physical form—some towns getting good classrooms, others stuck with delays and substandard work.

So Albay needs a simple, practical categorization of LGUs, with clear indicators.

Tier A — Implement-ready

LGUs with functioning engineering and procurement capacity, track record, and quality control systems. They can implement directly, with standard oversight.

Tier B — Implement-with-assistance

LGUs that can implement but need technical support and stronger systems. Provide provincial engineering support, standard designs, coaching, and shared procurement tools.

Tier C — Not yet implement-ready

LGUs with weak technical capacity or high procurement risk. Don’t force them into full implementation. Use pooled delivery: provincial-led project management, inter-LGU arrangements, or bundled implementation with strict monitoring.

This is not about shaming weaker LGUs. It’s about being realistic so the poorest areas don’t end up with the worst classrooms—again.

Guardrail 4: Community participation—as implementor, monitor, or both

If classroom projects are meant to serve communities, communities must have a meaningful role—not as ceremonial “stakeholders,” but as active partners who help protect the project from delays, shortcuts, and questionable decisions.

We already have proven Philippine models:

- Inter-LGU collaboration models like PALMA show how alliance approaches can pool resources and strengthen delivery even where one LGU alone may struggle.

- KALAHI-CIDSS demonstrates that communities can take real roles in planning, implementation, and oversight through a structured community-driven process.

- Citizen monitoring models like CCAGG show that ordinary citizens, when organized and trained, can spot substandard materials, inflated costs, and compliance issues.

The point is not to copy these models wholesale—but to adopt their core lesson:

projects improve when citizens have real roles and real access to information.

What “success” should look like by SY 2026–2027

This policy will not be judged by the signing of agreements or the announcement of budgets. It will be judged by one simple outcome:

Are the classrooms usable—on time—safe— and built well enough to last?

To make that measurable, Albay can adopt a Classroom Delivery Scorecard that tracks:

- readiness tier classification (A/B/C)

- procurement speed + compliance

- physical progress vs timeline

- inspection findings + defect correction rate

- transparency compliance (public posting and updates)

- community monitoring feedback and action taken

- turnover quality and post-turnover defects

Reform—with conditions

Classrooms to LGUs can work. In fact, it can be one of the most practical examples of devolution delivering visible results.

But only if we treat it as governance reform—not merely budget transfer.

Because if the guardrails are missing, the risk is predictable:

we don’t fix classroom delays—we simply relocate them.

We don’t reduce corruption risk—we simply decentralize it.

We don’t improve equity—we widen the gap between LGUs that can deliver and LGUs that cannot.

So yes—reform in motion is possible. But only if Albay insists on four guardrails: firm standards, radical transparency, capacity-based LGU clustering, and strong community participation.

Because in the end, the public won’t ask who implemented it.

They will ask: May classroom na an mga aki? Ligtas sinda?

Leave a comment