History often remembers the loudest voices—the speeches, the victories, the grand gestures. Yet some of the most enduring legacies are carried quietly, in court filings written late at night, in cases taken without payment, and in lives lived far from comfort. The story of Atty. Hermon “Mon” Lagman belongs to this quieter kind of heroism, where law was not merely a profession but a moral commitment.

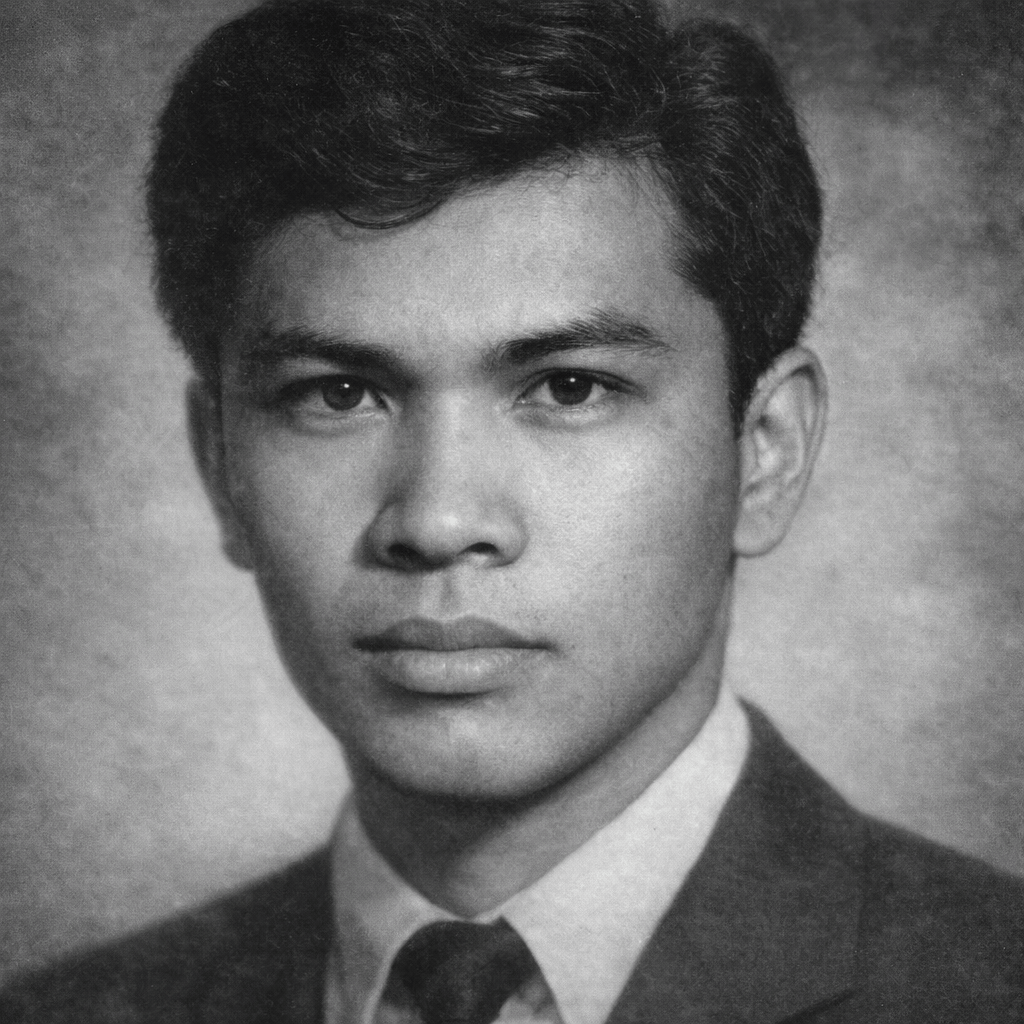

Born on February 14, 1945, Lagman came of age in a Philippines marked by social unrest and widening inequality. As a student at the University of the Philippines, he entered a tradition of intellectual dissent and public engagement. His time with the Philippine Collegian—long a crucible for critical thought—revealed not only a sharp legal mind but a conscience already attuned to injustice. For Lagman, education was never meant to distance him from the struggles of ordinary people; it was meant to bring him closer to them.

Instead of pursuing the safer and more lucrative path of private legal practice, Lagman helped build what would become one of the country’s most important human-rights institutions: the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG). In the tense atmosphere of the Marcos dictatorship, this was not simply a professional choice. It was a declaration. FLAG lawyers defended political detainees, labor organizers, and marginalized citizens at a time when doing so invited surveillance, harassment, and danger. To stand beside the accused in those years was to stand against fear itself.

What distinguished Lagman was not only courage but empathy—an empathy that reshaped how law could serve the poor. He was known to write pleadings in Tagalog so workers could understand the very cases filed in their defense, breaking the barrier between legal language and lived reality. He gave money for meals, transport, and medicine when justice required more than argument. In these small, human gestures, the distance between courtroom and conscience disappeared.

Such choices carried consequences. During martial law, defenders of labor and civil liberties were often treated as enemies of the state. Arrests, intimidation, and enforced disappearances formed part of a wider pattern meant to silence dissent. On May 11, 1977, Lagman vanished along with his associate while on the way to a meeting in Pasay. Like many desaparecidos of that era, his fate was never officially explained. Absence became the final record.

Yet disappearance did not erase him. His name now stands on the Wall of Remembrance at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, among Filipinos who resisted authoritarian rule. Memorials such as this do more than preserve memory; they ask each generation what courage looks like in its own time. Lagman’s life answers quietly: courage may be choosing the poor when power demands silence, or choosing truth when comfort is easier.

Today, the institutions he helped shape continue to defend rights in courtrooms across the country. Young lawyers still take on unpopular cases. Workers still seek justice in languages they understand. In these continuing struggles, Lagman’s unfinished work persists—not as nostalgia, but as responsibility.

To remember Mon Lagman is not only to honor sacrifice. It is to confront a question that outlives any single era: what is the law for, if not the protection of human dignity? His life suggests that the real measure of justice lies not in statutes or verdicts, but in whether the most vulnerable can stand unafraid.

Between courtrooms and conscience, he chose conscience—and in doing so, ensured that even in silence, his voice would endure.

Leave a comment