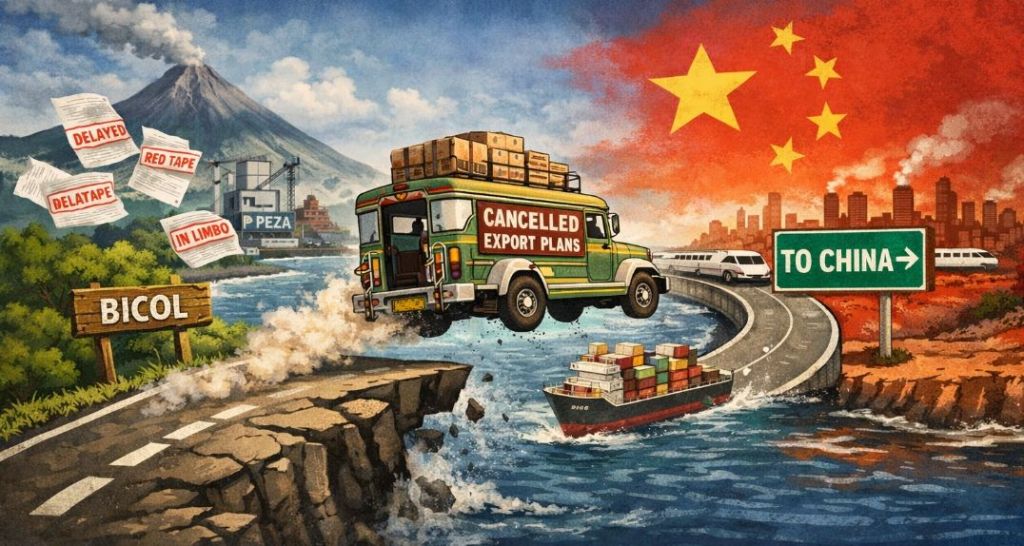

Bicol didn’t lose a ₱52.11-billion investment because it lacked land, labor, or ambition. It lost it—at least for now—because the national government’s investment process can still turn a “yes” into a long, costly “maybe.”

Francisco Motors LLC has paused its planned ₱52.11-billion special economic zone project in Bicol—described in reports as the biggest investment approved by the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA) in 2024—and is shifting attention to its China factory in the meantime. That decision should worry anyone who claims to support countryside growth, industrialization, and jobs outside the usual economic centers.

Because the punchline here is brutal: the investment didn’t disappear. It simply went where decisions move faster.

Approved but not approved

The project had the kind of headline attributes policymakers love: scale, jobs, new technology. PEZA’s own listings show a Jose Panganiban Special Economic Zone in Camarines Norte (the location tied to the investment narrative) as a manufacturing ecozone. Reports about the Francisco Motors investment also point to Jose Panganiban, Camarines Norte as the site of the proposed ecozone, with a commitment around ₱52.5 billion—large enough to surpass other marquee projects that year.

Yet “approved by PEZA” did not translate into the kind of certainty investors expect. The company’s chairman, Elmer Francisco, was quoted saying they faced “major roadblocks” after PEZA board approval—specifically citing the Fiscal Incentives Review Board (FIRB)—and said their repeated requests for an audience with the President were ignored.

Whether one agrees with the company’s framing or not, the signal is unmistakable: post-approval uncertainty became expensive enough to freeze a ₱52-billion commitment.

Costly Indecision

Investors can live with strict rules. What they cannot live with is a moving target.

The modern investment decision is a race between countries, and the finish line is not the press release; it’s the groundbreaking, the construction schedule, the supply contracts, the hiring plan. The moment an investor senses that approvals can be re-litigated, incentives reshaped midstream, or timelines stretched without clear resolution, capital becomes allergic.

That is why this episode matters beyond Bicol. It shows how national agencies can unintentionally punish the regions through a familiar pattern:

One arm of government signals “come in.”

Another arm signals “wait.”

A third arm signals “not like that.”

And the investor, reading the whole system rather than one agency, says: we’ll build somewhere else first.

The reports say that “somewhere else,” for now, is the company’s China factory.

What Bicol Actually Lost

A ₱52-billion manufacturing investment isn’t just a factory. It’s an ecosystem:

direct jobs inside the plant,

indirect jobs in construction, logistics, and services,

supplier networks for parts and components,

skills pipelines with local schools and training centers,

and a credible anchor for industrial clustering.

For a region that often gets discussed only in the context of disasters, poverty rates, and out-migration, a serious industrial project is a rare chance to change the storyline: from “resilience after calamity” to “prosperity through production.”

When the project pauses, the region doesn’t just lose future wages. It loses momentum, bargaining power, and confidence—especially the confidence that national systems will back up their own regional development rhetoric.

The real problem: national agencies struggle to choose a priority

This is the part officials rarely admit: the national investment regime frequently tries to serve two masters at once.

On one hand, it wants to attract investors—especially those bringing high-value jobs and technology. On the other, it keeps layering review, re-review, and shifting interpretations that make the “yes” feel provisional.

That behavior is often defended as prudence. But when prudence turns into paralysis, it becomes anti-development policy disguised as process.

And it hits the regions hardest.

Large investors who can relocate easily will choose certainty elsewhere. Smaller local enterprises who cannot relocate will stay—and absorb the cost of indecision quietly, year after year. Either way, the regions pay.

What would “prioritizing local economic development” look like?

Not slogans. Not events. Not another glossy roadmap.

It would look like three basic disciplines:

- One government voice after approval. Once a project clears PEZA and the required fiscal gates, agencies should behave like the decision is settled—not like it’s a debate continuing in slow motion.

- Time-bound, transparent incentive processing. Investors don’t need favors; they need predictability. If incentives require review, set deadlines, publish rules, and enforce internal accountability when timelines slip.

- Region-first clarity for region-changing projects. If national government says it wants inclusive growth, then mega-investments in the regions should trigger a “fast lane” of coordination—not a maze.

Bicol’s lesson is not that the regions are unready. Bicol’s lesson is that when national agencies don’t know what to prioritize, local development becomes the first sacrifice—quietly, efficiently, and expensively.

Leave a comment