With around 54 recorded eruptions since written records began in 1616, Mayon Volcano is the Philippines’ most active volcano—and one of the most consistent “auditors” of governance the country has ever had.

Over more than four centuries, Mayon’s eruptions didn’t just reshape slopes and river channels. They steadily rewrote the rules of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM)—from an era when disasters were measured in graves, to a time when the main life-saving tool is moving people early, and sustaining them safely while they’re displaced.

What follows isn’t a full eruption-by-eruption narration (the official catalogs already do that). It’s a map of the moments that changed the playbook—and why they mattered.

The early record: Mayon was always dangerous; we were just slower to learn

The first cataloged eruptive period in the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program (GVP) record is 1616 (Feb 19–23), and it already includes the hazards modern DRRM planners fear most — pyroclastic flows and lahars/mudflows, not merely ashfall and lava.

That matters because it punctures a common illusion: that the volcano became more dangerous later. It didn’t. What changed was the system built around it.

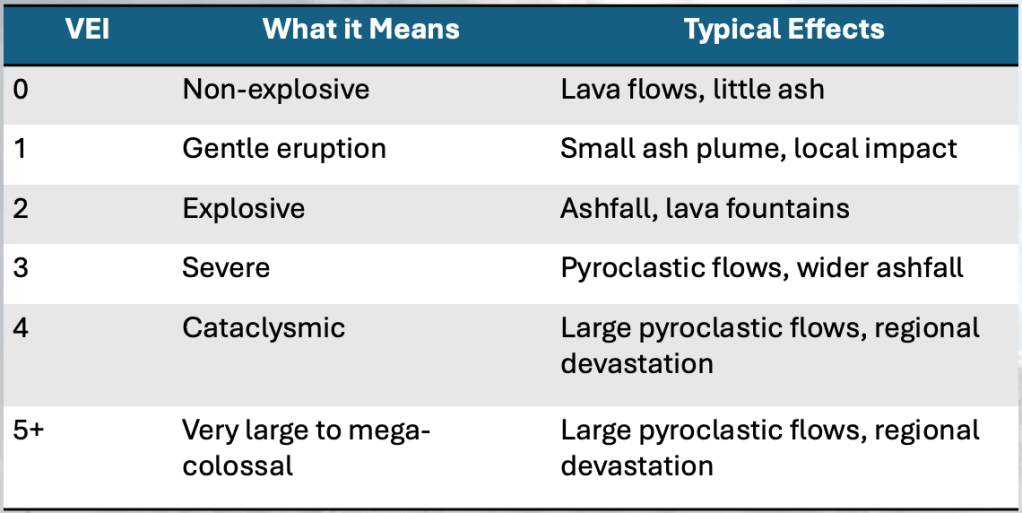

A second early clue comes from 1766 (July 20–25). The eruption is recorded as Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 3, but the record also flags fatalities on Oct 23, 1766, a detail that reads like an early DRRM memo from the past: risk doesn’t end when the eruption calms down—rain can remobilize deposits into deadly mudflows months later. VEI is a logarithmic scale that ranks eruptions by explosiveness and erupted volume.

By 1800 (Oct 30–31), the record again flags fatalities, reinforcing that Mayon’s lethal potential was not a one-time tragedy waiting for 1814.

Rule of the era (unwritten): survive if you can; rebuild if you must.

1814: The catastrophe that turned memory into a warning sign

The 1814 eruption became the most enduring symbol of Mayon’s worst-case scenario. Modern reporting still cites it as killing about 1,200 people, and the ruins of Cagsawa remain a cultural shorthand for “this can happen again.”

In DRRM terms, 1814 represents a governance reality that would persist for generations: disasters were recorded mainly through death and destruction, because prevention systems were limited and displacement wasn’t managed as a deliberate life-saving strategy.

Rule learned (slowly): you can’t rely on memory alone; you need rules.

1984: When evacuation became policy—not panic

By 1984, the story begins to sound like modern DRRM. Scientific monitoring informed decisions, and the core tactic wasn’t bravery—it was movement. A GVP SEAN report described evacuees swelling to more than 73,000 across multiple centers, with no casualties attributed directly to the eruption or mudflows in that reporting.

This is a pivotal rewrite of the disaster playbook: evacuation at scale became not just acceptable, but expected.

Rule rewritten: Displacement can be a success metric when it prevents death.

1993: When science was right—but people still died

On 2 February 1993, Mayon’s pyroclastic flows killed 77 people, a figure stated in PHIVOLCS’ retrospective and echoed in a UN humanitarian information report preserved on ReliefWeb.

1993 is not just a volcanic event. It’s a governance lesson: warning systems are only as effective as compliance—and compliance depends on livelihoods, incentives, and enforcement. People do not evacuate on hazard maps alone. They evacuate when leaving is survivable—economically, socially, and politically.

Rule upgraded: Risk communication must be matched by livelihood-sensitive enforcement and support.

2000: The most disruptive eruption—because it became a marathon

If 1993 is a lesson in lethal speed, 2000 is a lesson in institutional endurance. The disruption wasn’t one terrible day; it was weeks of shelter management and repeated decision-making under uncertainty.

OCHA situation reports tracked the burden in numbers:

- March 7, 2000: 14,114 families (68,426 persons) housed in 52 evacuation centers.

- March 23, 2000: evacuees had reduced to 5,751 families (27,849 people) still living in 24 centers—a sign not of “problem solved,” but of a prolonged, expensive tail of displacement.

This is where DRRM becomes less about dramatic rescue and more about boring-but-essential systems: sanitation, health surveillance, education continuity, protection risks, and financing—sustained long after the eruption headlines fade.

Rule rewritten: DRRM must manage time and continuity, not just hazard zones.

2013: The “small” eruption that still killed

Mayon’s 2013 phreatic eruption is remembered because it killed five climbers near the summit—during what many would interpret as a less dramatic hazard phase.

This forced a different kind of DRRM maturity: risk isn’t only for residents and farmers. It includes visitors, tourism activity, access controls, and the governance courage to say: “No, you can’t go there.”

Rule expanded: Calm-looking does not mean safe; exclusion zones must be enforced.

2023: Modern DRRM—where displacement is tracked, managed, and still costly

By 2023, Mayon’s eruption management included constant quantification. DSWD’s DROMIC report (as of 21 Sept 2023, 6PM) recorded 3,474 families (12,331 persons) staying in 22 evacuation centers in Albay, alongside broader “affected” tallies.

Modern DRRM can prevent mass death—but it cannot pretend displacement is painless. Prolonged evacuations become their own governance challenge: sustaining dignity, services, and recovery pathways, not merely keeping people alive.

Rule refined: Preventing deaths is success; preventing long-term displacement harm is the next frontier.

2026: A “quiet eruption” and a loud reminder

In early January 2026, AP described Mayon entering a “quiet eruption” phase—yet still requiring thousands to leave. AP reported more than 2,800 evacuated from the permanent danger zone plus about 600 voluntary evacuees outside it.

Even without cinematic lava curtains, the system still had to do the same hard thing: move people early based on credible risk.

Rule reaffirmed: Don’t wait for spectacle; act on risk.

What Mayon changed in DRRM—across four centuries

Across this arc, Mayon rewrote the rules in five durable ways:

- From memory to monitoring (the hazard was always there; evidence became clearer)

- From death counts to evacuation doctrine (1984 as a proof point)

- From warnings to behavior + livelihoods (1993’s lesson)

- From emergency response to continuity management (2000’s “marathon” reality)

- From hazard management to multi-risk governance (lahars and delayed impacts hinted as early as 1766)

Mayon repeats. The real question is whether institutions keep improving faster than fatigue sets in—because in DRRM, the most dangerous outcome isn’t eruption. It’s complacency dressed up as familiarity.

References

- Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program (Mayon eruptive history; early periods 1616, 1766, 1800).

- Associated Press (Jan 7, 2026): notes Mayon’s eruption frequency since 1616; 1814 fatalities and 2026 evacuations.

- GVP SEAN report (Sept 1984): evacuees exceeded 73,000; no casualties attributed in that report.

- PHIVOLCS retrospective on 1993: 77 deaths within 6-km radius.

- UN humanitarian information report on 1993 (ReliefWeb): 77 dead tally in situation reporting.

- OCHA situation reports (Mar 7 & Mar 23, 2000): evacuation center counts and evacuee totals.

- GVP BGVN report (2013): phreatic eruption killed five climbers.

- DSWD DROMIC Report #80 (Sept 21, 2023): evacuee numbers in Albay.

Leave a comment