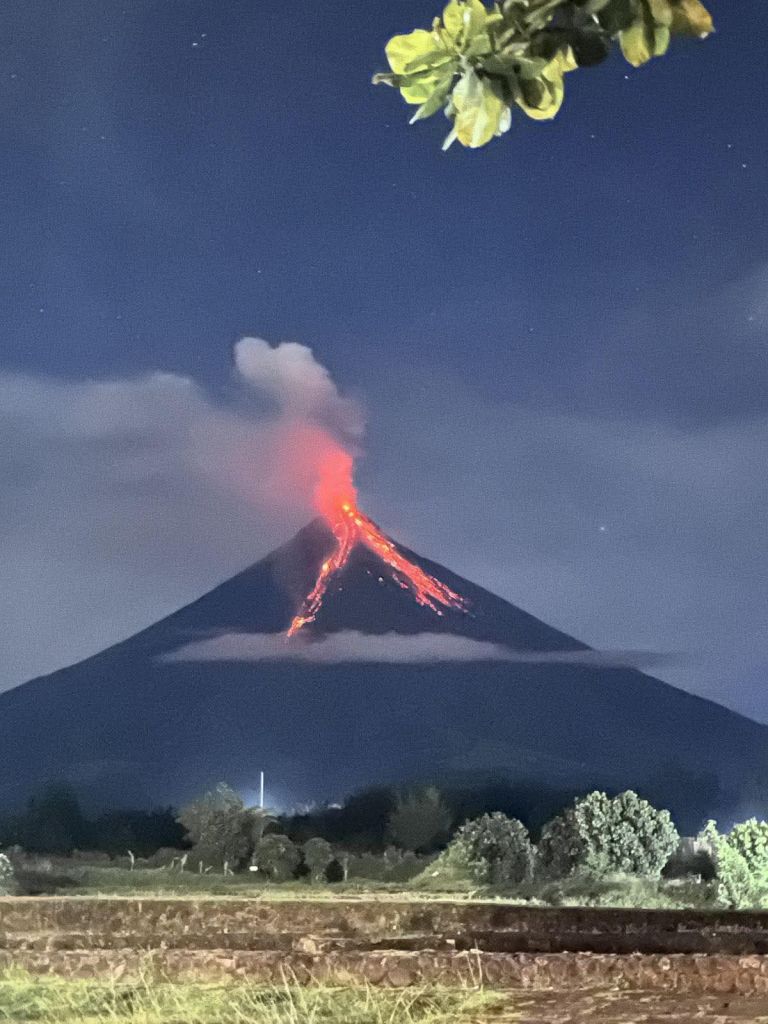

In the past several days, Mayon Volcano has been spewing ash and pyroclastic materials—no, not the Mayon in Naga City, but the active, perfectly coned volcano in Albay. And when Mayon starts acting up, we do what we always do: raise alert levels, move people out, stock evacuation centers, watch the gullies and river channels for lahars, and refresh the public on what a “danger zone” actually means.

And then—because we’re human—we also do what we always do: act surprised.

This week’s renewed unrest (with Alert Level 3 raised by PHIVOLCS and evacuations in Albay) is a reminder that disaster risk governance is not just about volcano monitoring. It’s about memory management—the ability of a society to remember risk clearly enough to make boring, disciplined decisions before the ash starts falling. The map that basically says: “We’ve been here before.”

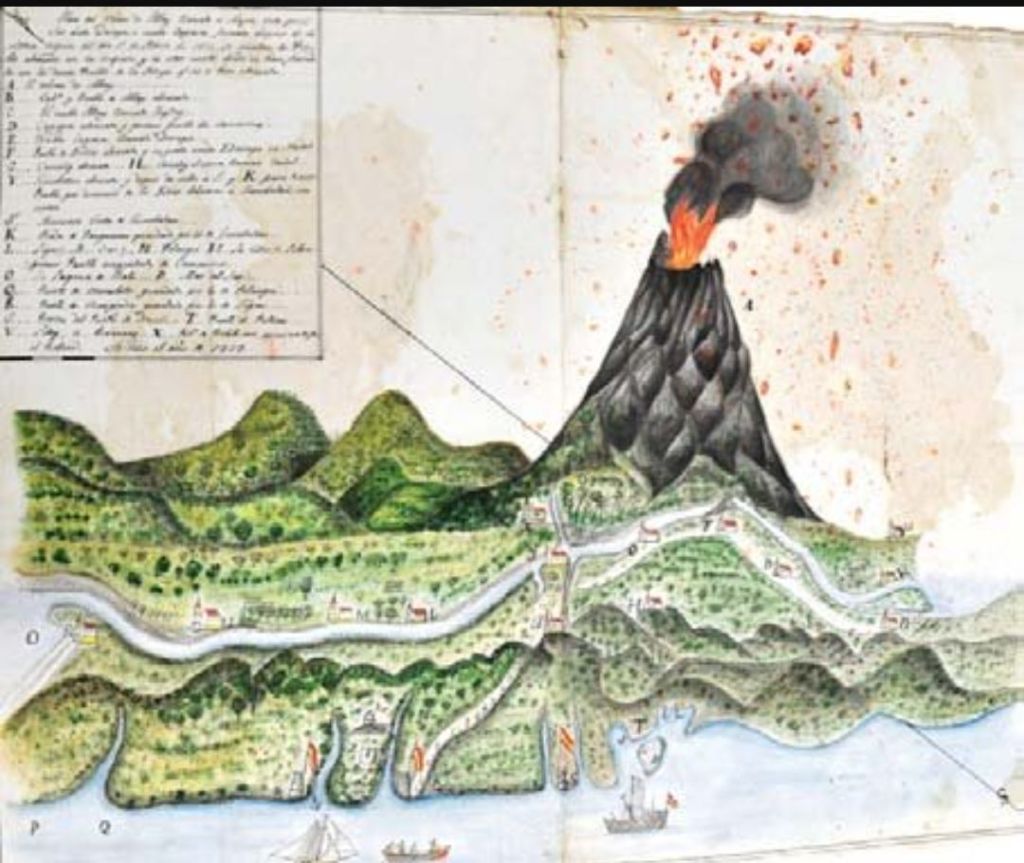

Long before dashboards, hazard maps, and press briefings, there were people who recorded disasters the old-fashioned way: by drawing them. One of the most striking historical records of Mayon is an 1839 Spanish-era map titled Volcán de Albay (cataloged as AFIO 94/41 (II)). Research on Franciscan mapping in the Philippines identifies and reproduces this very piece, showing how the territory around Mayon was represented and understood in the 19th century.

What makes it powerful isn’t just the sketch of a perfect cone. It’s the legend of place names—communities laid out around the volcano: Cagsaua (Cagsawa), Camalig, Libon, Laguna de Bato (Lake Bato)—a quiet but blunt message: these are the people around the hazard; plan accordingly.

That is disaster risk governance in embryo.

Historical records do what warnings sometimes can’t: they make risk “real”

Modern risk communication often fails because it’s abstract. “6-kilometer Permanent Danger Zone” is accurate, yes—but it can still feel like a technical phrase floating above daily life.

Historical records fix that problem in three ways. First, they preserve institutional memory when leadership rotates. Disasters are seasonal; governments are rotational. When mayors change, when officers get reassigned, when attention moves elsewhere, the risk does not politely wait. Records like the 1839 map serve as long-term institutional memory—a durable reminder that these towns, routes, and river systems have been in Mayon’s story for centuries.

Second, they anchor risk in named communities, not just zones. People don’t evacuate “hazard polygons.” They evacuate barangays, farms, schools, churches, and homes.

The famous 1814 eruption associated with the destruction of Cagsawa is still part of public memory today—sometimes simplified, sometimes debated in detail—but it remains a historical marker of what Mayon can do to settlements that sit in its path. When a historical map names the communities around the volcano, it strengthens a governance truth: risk is geographic, but vulnerability is social—it has names and addresses.

Third, they expose repeat mistakes (the hardest lesson). The uncomfortable value of history is that it lets you compare yesterday’s disaster geography with today’s settlement patterns and ask:

Are we reducing risk—or just getting better at evacuating the same places again and again?

Right now, PHIVOLCS bulletins and reporting describe ongoing hazards like rockfalls and pyroclastic density currents and reiterate the Permanent Danger Zone concept—because the threat is not theoretical.

If we keep returning people to the same high-risk spaces with the same exposure, then what we have is not resilience. It’s a well-practiced routine.

The Sendai Framework basically agrees: understanding risk is Priority #1. Globally, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) puts “Understanding disaster risk” and strengthening risk governance at the center of effective DRR. That’s not just about sensors and models; it also includes collecting, using, and communicating risk knowledge—including historical risk knowledge.

In plain language: if a society can’t remember clearly, it can’t govern risk well.

So what should we do with an 1839 map in 2026?

Not worship it, of course. Use it.

Here are practical ways historical records strengthen disaster risk governance today:

- Prepare better public risk communication. Pair a modern PHIVOLCS hazard map with an annotated historical map in LGU advisories or museum-style posters. People absorb risk faster when they see continuity.

- Develop land-use discipline with receipts. Historical records support hard conversations about no-build zones and resettlement by showing that danger footprints are not invented by the current administration.

- Ensure that education that sticks. Teach Mayon risk as a community story across generations (places, routes, rivers, evacuation patterns), not as a one-time “science lecture.”

- Develop appropriate policies — and with humility: History helps leaders say the honest line: “Mayon is not misbehaving; Mayon is being Mayon.” The job is to govern accordingly

Because the volcano has a long memory. The question is whether we do.

References

- Bacolcol, T. (as quoted in Associated Press). (2026, January 7). Philippines evacuates 3,000 people after activity increases at Mayon Volcano. Associated Press. �

- DOST-PHIVOLCS. (2026, January). Mayon Volcano Bulletin / PHIVOLCS-LAVA bulletins (Alert Level 3; hazards including rockfalls, PDCs; PDZ guidance).

- Luengo Gutiérrez, P. (2011). Los franciscanos y la representación del territorio en Filipinas entre los siglos XVII y XIX. Anales del Museo de América, 19, 122–139. (See figure: AFIO 94/41 (II). Volcán de Albay (1839).)

- UNDRR. (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- UNDRR. (n.d.). What is the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction?

- CBCP News. (2014/2015, as archived online). Old pics show Mayon church not buried, says historian.

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Cagsawa Ruins. (For overview of dates, historical spelling “Cagsaua,” and association with the 1814 eruption; use cautiously as a secondary summary.)

- Philstar. (2026, January 10). Mayon Volcano sends lava, pyroclastic flow downslope as dome collapses.