Long before “local history” became fashionable—and even longer before regional pride found its way into hashtags—Jose Calleja Reyes was already doing the hard, patient work of remembering. Not the sentimental kind of remembering, but the disciplined, archival, footnote-heavy kind that insists a region’s past deserves more than a passing mention in a Manila-centered narrative.

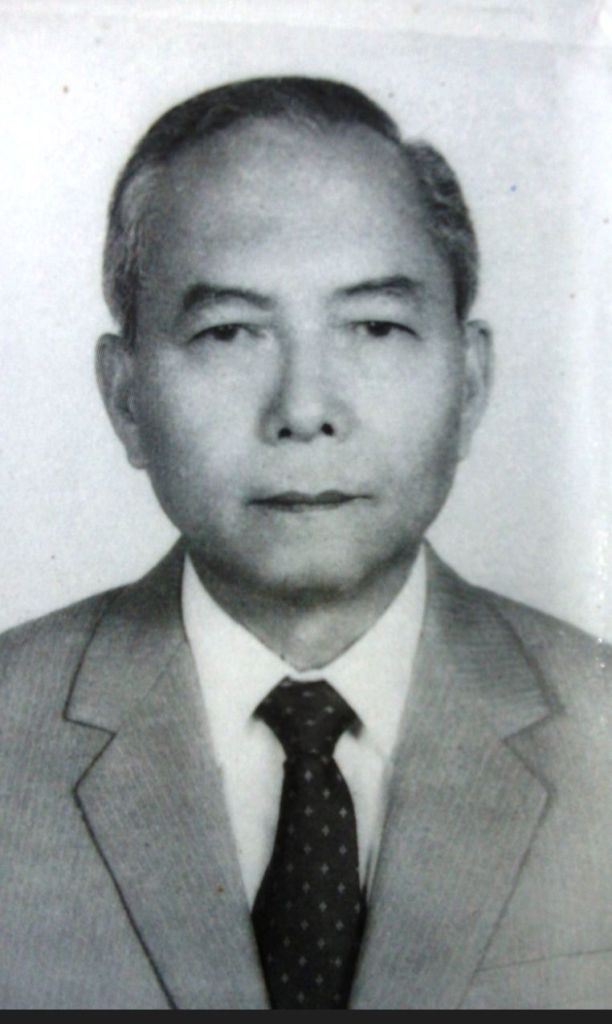

Born on 30 December 1926 in Legazpi City, Reyes grew up in Bikol at a time when provincial histories were often treated as sidebars to a larger “national story.” Genealogical records identify his parents as Marcial Rábago Reyes and Dolores Malonda Calleja, rooting him firmly in Bikol soil before life and career later pulled him to Manila and other places. In 1954, he married Elvira Garcia Guidote, and together they raised ten children—an impressive feat in itself, considering the scale of Reyes’s intellectual output.

By training, Reyes was a lawyer. By inclination, he was much more. He practiced law, engaged in business, and yet consistently returned to questions that rarely paid well but mattered deeply: Who were the Bikolanos before colonization? How were their stories preserved—or distorted—by colonial records? And what happens when a people forget the rigor required to tell their own history?

One of Reyes’s most important scholarly interventions came in 1968, with his article “Ibalon: An Ancient Bicol Epic,” published in Philippine Studies. Rather than treating Ibalon as mere folklore, Reyes analyzed it as a historical and cultural text—layered, mediated, and shaped by both indigenous memory and colonial transcription. He showed that epics are not frozen myths but living narratives, vulnerable to loss when they are romanticized instead of studied. Long before “decolonizing knowledge” became academic shorthand, Reyes was already practicing it.

If Ibalon was the gateway, Reyes’s most ambitious work was Bikol Maharlika, published in 1992. Spanning more than 500 pages, the book is part ethnography, part historical narrative, and part cultural reckoning. Reyes explored early Bikol society, belief systems, language, rituals, and responses to Spanish colonization with a seriousness usually reserved for national histories. It is not light reading—and that, precisely, is the point. Reyes understood that treating Bikol history lightly was one of the reasons it kept being sidelined.

Beyond this landmark volume, Reyes contributed essays to academic and ecclesiastical publications, including detailed studies of early Spanish contact and evangelization in the Bikol region. These writings reveal a scholar willing to engage uncomfortable intersections—religion, power, and colonial authority—without reducing them to slogans. Throughout his work, Reyes balanced accessibility with rigor, convinced that history could be made readable without being made shallow.

Reyes belonged to a broader 20th-century movement of Bikol writers and scholars who asserted regional identity through scholarship rather than spectacle. He was not primarily a novelist or poet, but his historical writing performed a literary function of its own: it insisted that Bikol had a past complex enough to demand attention and a present confident enough to claim it.

He passed away on 1 April 1994 in Quezon City, but his legacy endures—in classrooms, footnotes, heritage debates, and the growing confidence of Bikol scholarship that no longer asks permission to speak.

Why Reyes Still Matters

In a time when speed often replaces substance, Jose Calleja Reyes reminds us that memory requires discipline. He showed that regional history is not a decorative appendix to national narratives but a foundation that reshapes them. By treating Bikol’s epics, encounters, and transformations with seriousness, Reyes made a quiet but firm argument: a people who know their history are harder to erase, harder to misrepresent, and harder to reduce to a footnote.

And that may be his most lasting lesson. Bikol is not a footnote—not because it is loudly proclaimed, but because scholars like Reyes took the time to prove it.

References

Realubit, Maria Lilia F. Bikol Literary History. Naga City: Bikol Heritage Society, 2001.

———. Bikols of the Philippines. Naga City: AMS Press, 1983.

———. “Bikol Literature in the Philippines.” National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA). Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://ncca.gov.ph/about-ncca-3/subcommissions/subcommission-on-the-arts-sca/literary-arts/bikol-literature-in-the-philippines/

Reyes, Jose Calleja. “Ibalon: An Ancient Bicol Epic.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 16, no. 2 (1968).

https://doi.org/10.13185/2244-1638.2279

———. Bikol Maharlika. Quezon City: JMC Press, 1992.

———. “Portrait of the Bikols at Spanish Contact and the First Seven Decades of Their Evangelization.” Boletín Eclesiástico de Filipinas 52, nos. 579–580 (February–March 1978). University of the Philippines Diliman Rare Periodicals Repository.

https://repository.mainlib.upd.edu.ph/omekas/s/rare-periodicals/media/252061

FamilySearch. “Jose Calleja Reyes (1926–1994).” Accessed December 28, 2025.https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LR39-K24/jose-calleja-reyes-1926-1994

Leave a comment