A few months back, I had a client who commissioned a pre-election survey last November, way before the campaign period officially began. The results weren’t exactly confidence-boosting: he was trailing the incumbent by over 10 percentage points, with a ±5% margin of error. Fast forward to election day, and surprise! He won by 6%. Now he’s refusing to pay, convinced the survey was wrong, and I’m left dealing with an angry field team asking where their honoraria went.

So… was the survey wrong?

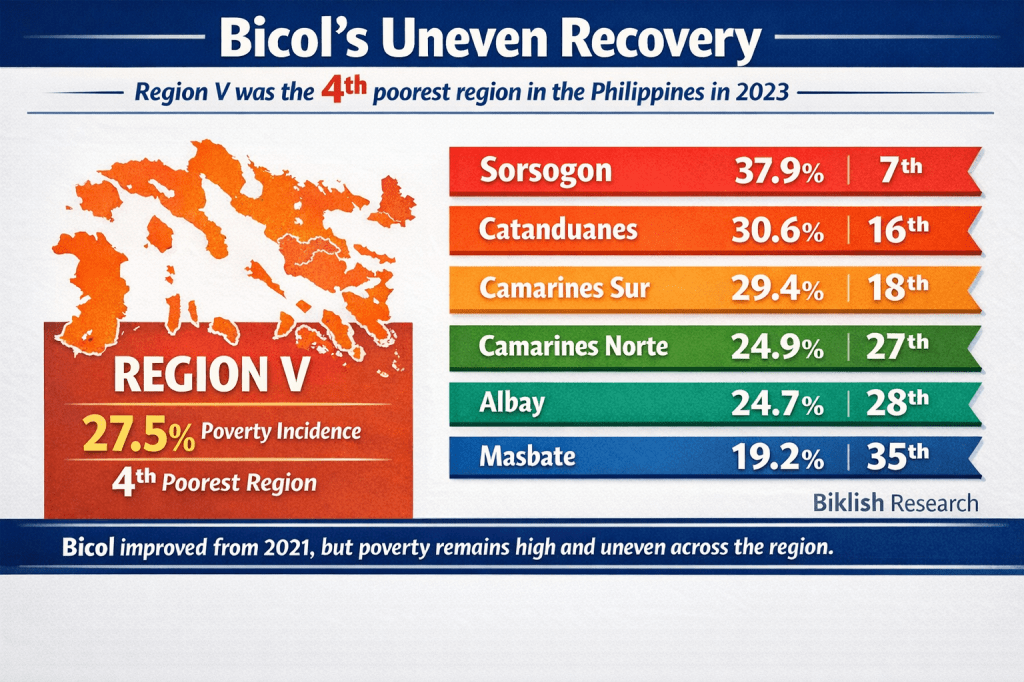

That’s the question many people are asking, especially after the 2025 elections. From barangay halls to the Senate chamber, the credibility of survey firms has taken a hit. Major players like Social Weather Stations, Pulse Asia, and even Octa Research missed big time on some names. Rodante Marcoleta, Kiko Pangilinan, Bam Aquino, even Imee Marcos—all made it to the Magic 12 despite barely scraping survey rankings.

But before we grab our pitchforks and declare these surveys as fake news, let’s pause and ask: Were the surveys really conducted to predict the results? Or are we just using them wrong?

1. Surveys Aren’t Fortune Tellers. They’re Snapshots.

Imagine taking a selfie in November and expecting it to still reflect reality in May—filters, lighting, and all. That’s exactly what happens when we treat early surveys as gospel truth. Voter preferences shift. Endorsements drop. Candidates trend—for good or cringey reasons. Political tectonics move. And in that whirlwind, a 10-point deficit can flip into a 6-point lead—especially if the ground campaign is firing on all cylinders.

As political analyst and former NAPC Secretary Dr. Joel Rocamora aptly put it: “A survey is like drawing a glass of water from the middle of a flowing river. Even if you scoop from the same spot, it won’t be the same water.” In other words, surveys are snapshots of moving targets. Just like you can’t step into the same river twice, you can’t expect a November poll to predict a May election.

2. Survey Samples Aren’t Magic.

If the sample misses key voter segments—like rural communities, undecided voters who make up their minds in the last week, or the so-called “silent majority” who avoid political discussions like the plague—you don’t get a complete picture. You get a selfie with half the face cropped out.

Even the most reputable polling firms can trip over sampling bias. Maybe they surveyed too many from urban areas but not enough from provinces where barangay leaders still hold sway. Maybe they missed voters who don’t have internet access or landlines, or those who simply don’t pick up unknown numbers. That’s not just a gap—it’s a gaping hole in representation.

Then there’s the psychology of it all. Some voters, especially in tight-knit communities or judgmental online circles, won’t say who they’re really voting for. They’ll smile, nod, and say the “acceptable” choice—but mark a completely different name on the ballot. It’s called social desirability bias—where respondents give answers they think are more socially acceptable, even if they’re not true. So a candidate branded as corrupt, crass, or “baduy” may fly under the radar in surveys, but quietly build a stealth army of supporters who only reveal themselves on election day. Just like Sol Aragones, an former ABS-CBN news reporter who, on the last leg of the campaign period endorsed Marcoleta — the then Congressman who “killed” the media giant and caused the loss of jobs of around 11,000 employees and budding talents.

In short, surveys are only as good as the people you ask—and only if they’re telling you the truth. That’s why firms like Solistrat, Inc. have started integrating validation questions and layered probes into their survey tools—not to interrogate respondents, but to peel back the polite answers and get to what people actually think and feel. Because capturing public opinion isn’t just about asking questions—it’s about asking them right, and reading between the lines.

3. There’s a Lot Surveys Don’t See.

Surveys won’t catch the quiet but deadly power of barangay machinery. They won’t reflect how many kandidato finally got their act together two weeks before election day—scrambling to rally supporters, fix logistics, or ride the coattails of a last-minute endorsement. They won’t measure the sweat equity of volunteers knocking on doors, handing out flyers, or mobilizing neighborhood chats. And they definitely won’t pick up the influence of local personalities—those low-key kingmakers whose endorsements never make the headlines but sway entire precincts.

And here’s the part many people conveniently forget: most surveys are commissioned by the candidates themselves. And let’s be real—do you honestly think they’ll publish the ones where they’re getting clobbered? No candidate wants to look like a sinking ship days before election day. So what makes it to the press? The flattering ones. The morale-boosters. The “we’re leading, join the bandwagon” kind of surveys.

That’s why, at Solistrat, Inc., we always ask prospective clients one crucial question before taking on any political survey: “Are you commissioning this to shape a real, evidence-based campaign strategy—or just to manufacture momentum?” If it’s the latter, we respectfully decline. We don’t do propaganda. For elections, we generate data that as basis for strategies and plans that can help our clients win—not just trend.

4. Maybe the Real Problem Is Us, the Public.

We tend to treat surveys like spoilers—as if they’re supposed to reveal the ending before the story even unfolds. But that’s not what they’re designed for. Surveys are snapshots, not prophecies. They capture the mood at a specific point in time—not the entire arc of the campaign. They’re more like movie trailers: helpful in setting the tone, but rarely revealing the full plot. Unless it’s part of a continuous tracking series specifically designed to forecast results, a single survey can’t predict how the story ends. And in politics, the twist always comes late.

So were the surveys wrong?

Not exactly. But if you used them like a crystal ball, then yes—your expectations probably got crushed like a junked Comelec receipt.

If we want better accuracy, we need better data. More frequent surveys. Closer to election day. Exit polls. Deeper demographic slices. Until then, take those “Magic 12” lists with a sprinkle of salt… and maybe a side of actual grassroots organizing.

As for my client—if you’re reading this—the survey wasn’t wrong, bro. You just didn’t read the fine print.

Leave a comment