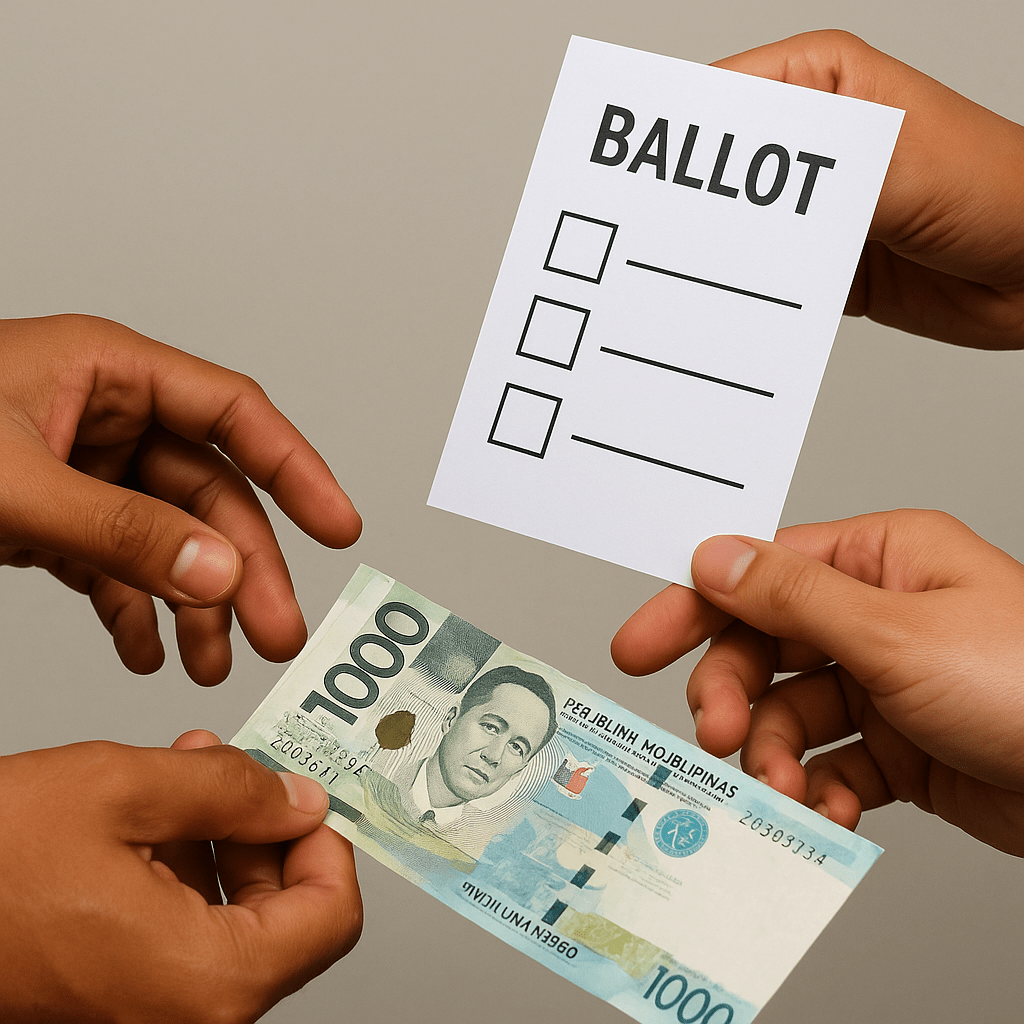

Do you know that some voters in Legazpi City were able to receive P22,500 in the recently concluded elections? Not from a single candidate, of course, but from different candidates. Does this mean the Legazpenos are “bobotantes”? Or does this mean the voter’s education that both the Commission on Elections and development organizations have been doing for decades is a failure?

Every election season, we’re flooded with the same old slogans: “Vote wisely!” “Don’t sell your vote!” “Choose leaders, not crocodiles!” But let’s be honest—those messages, while well-meaning, are like Band-Aids on a broken dam. Vote-buying isn’t just surviving; it’s thriving. From crisp bills inside envelopes to e-wallet transfers with campaign jingles, it’s become part of the system.

We always blame the voters. “One hundred pesos lang, nabibili na!” But that’s lazy thinking. It’s like blaming passengers for boarding a sinking ship when there are no other boats.

Here’s the real kicker: vote-buying persists not because people are ignorant, but because everyone—voters, candidates, and even political operators—are stuck in a game where doing the right thing could actually cost them everything.

Ever heard of the Nash Equilibrium? No, this isn’t your high school math trauma coming back. It’s a concept from game theory that explains how people make choices when everyone else is also making choices. In a Nash Equilibrium, no player has anything to gain by changing their strategy unless the others also change theirs.

Applying the Nash Equilibrium to our elections, we can have Peter and Paul as examples for vote-buyers. Peter knows that Paul is buying votes. If Peter doesn’t do it too, Paul gets the edge. Sharing the same logic, Voter Mary also knows that if she refuses the money, someone else will take it, and the same old trapo wins anyway. Hence, Peter buys votes, and Mary accepts. And everybody will say, “yan ang kalakaran eh” while the pundits call it “culture” and an indicator of poverty.

Worse, nobody wants to make the first move to break the cycle, because going solo is political suicide.

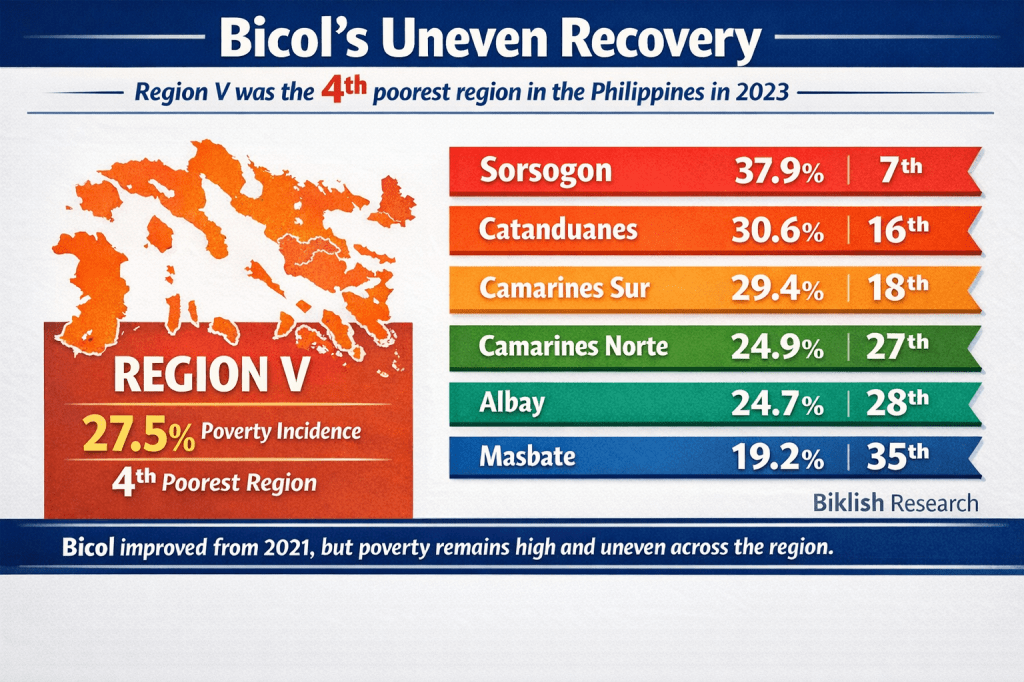

In this dirty game, everyone is playing rationally, but the outcome is irrational for society. We keep electing the rich, the corrupt, the dynasts. The real leaders? They can’t afford to play. Look at Dok Eddie Dorotan of Irosin, Sorsogon, whose track record went down the drain during the casting of ballots.

Let’s stop pretending this is a full democracy. If we’re being honest, what we have is something closer to what political scientists call a Selectocracy—a system ruled by a select few. Based on Selectorate Theory, real power doesn’t depend on the will of the majority, but on a tiny “winning coalition” made up of:

- Political dynasties,

- Wealthy campaign financiers,

- Regional powerbrokers, and

- Weak, personality-based political parties.

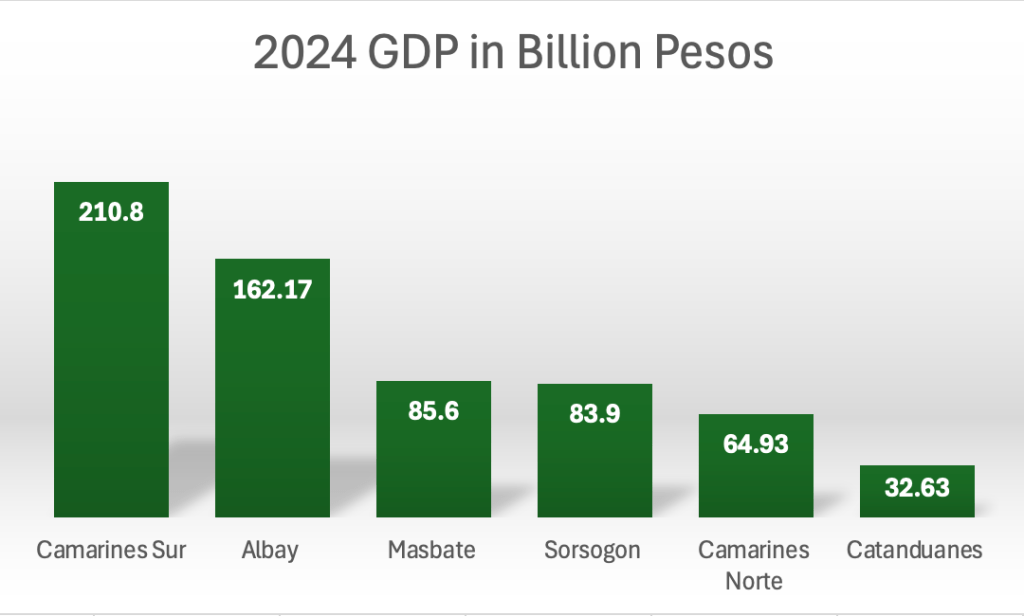

These are the gatekeepers. They decide who runs, who gets funded, and who wins. The rest of us? We just get to watch or sell our votes and hope our area gets a basketball court or a sack of rice in return.

Now, layer on Nash Equilibrium, and you’ll see why it’s so hard to break this cycle. Voters know accepting money isn’t ideal. Candidates know buying votes is shady. But unless everyone changes their strategy at the same time, nobody wins by doing the right thing alone.

So what happens?

Everyone stays in the game.

Everyone plays dirty.

And everyone loses—except the select few.

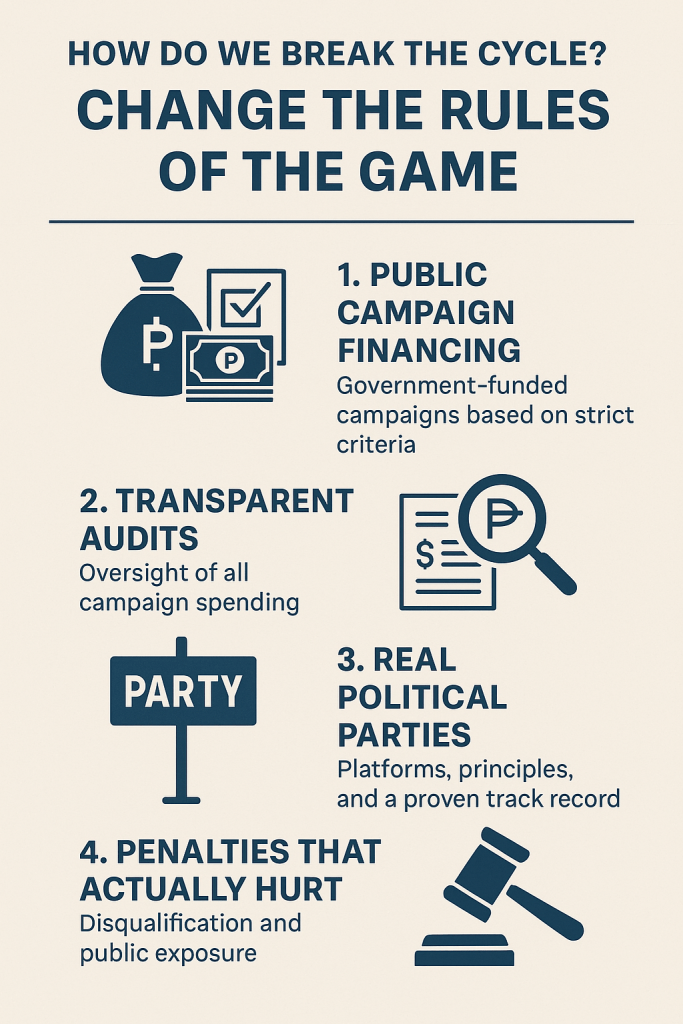

How Do We Break the Cycle? Change the Rules of the Game.

If we want elections to be about ideas—not allowances—then we need to stop blaming voters and start fixing the system. Here’s how we do it:

1. Public Campaign Financing. If we want cleaner elections, let’s start with cleaner funding. The government should provide campaign funds to political parties or candidates—based on clear, strict criteria. That way, no one has to go begging to shady donors who will later demand “return on investment” through overpriced projects or ghost contractors. Plus, with a set budget, candidates can’t just throw money around like confetti.

2. Transparent Audits. The beauty of using public funds? They come with strings attached—called accountability. The Commission on Audit, watchdog groups, and even regular citizens can monitor how every campaign peso is spent. If you’re spending our money, we have the right to check the receipts. Sunshine is still the best disinfectant.

3. Real Political Parties. To make sure public funds don’t end up in someone’s beach house or secret stash, we need real political parties—parties with platforms, principles, and a proven track record. None of these one-week-old shell parties formed just to beat the deadline. If a group hasn’t meaningfully existed and functioned for at least two years, sorry—not a real party. Candidates should also be bona fide members, not just last-minute adoptees. Otherwise? Automatic disqualification.

4. Penalties That Actually Hurt. Vote-buyers and sellers shouldn’t simply receive a slap on the wrist. Let’s strike where it hurts: disqualification from running, loss of party accreditation, and public naming-and-shaming. When the risk outweighs the reward, the system starts to shift. However, on another note, this may not be necessary if the first three are already implemented correctly.

It’s Not the Fish, It’s the Pond

Blaming the poor for accepting vote money is like blaming people for drinking dirty water when there’s no clean one around. If the system rewards money and punishes integrity, what do we expect?

The real challenge is this: we can’t just ask voters to be heroes in a system designed for the rich to win.

We need to change the rules, shift the equilibrium, and stop playing a game where the house always wins.

Leave a comment